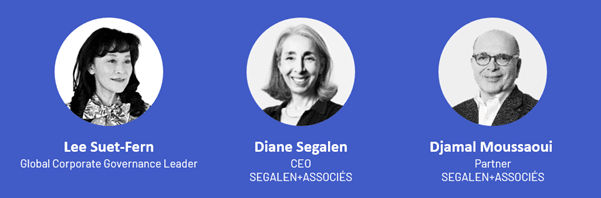

“European bords have made tremendous progress towards diversity”3 questions to Lee Suet-Fern, Global Corporate Governance Leader

12/11/2024

An accomplished lawyer and seasoned corporate governance expert, Lee Suet-Fern shared over three decades of experience advising Chairmen, CEOs, and major corporations across Asia-Pacific, Europe, and the United States.

As a highly respected Independent Board Member for numerous major public companies, she possesses deep insights into the unique governance structures of different regions and a strong understanding of geopolitical risk management. Known for her integrity, strategic thinking, and ability to foster constructive debate, Lee Suet-Fern has shaped the evolution of board governance and contributed to advancing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) principles globally.